Home >

Hartford circus fire in 1944...

Hartford circus fire in 1944...

Item # 557026

Currently Unavailable. Contact us if you would like to be placed on a want list or to be notified if a similar item is available.

July 08, 1944

THE NEW YORK TIMES, July 8, 1944

* Hartford circus fire

* The day the clowns cried

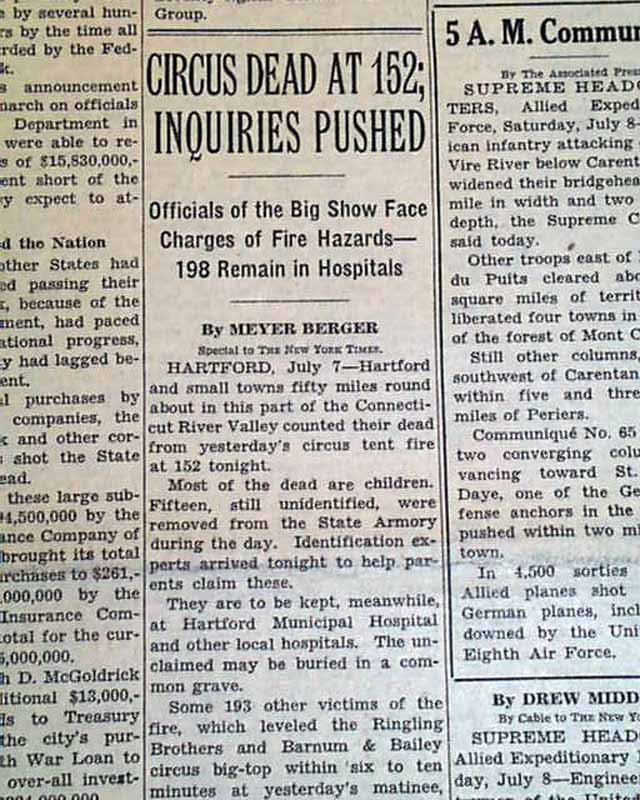

This 24 page newspaper has one column headlines on the front page: "CIRCUS DEAD AT 152;INQUIRIES PUSHED" "Officials of the Big Show Face Charges of Fire Hazards---198 Remain in Hospitals"

Continues on the back page with related photo. (see)

Other news of the day throughout. Light browning, otherwise in nice condition.

wikikpedia notes: The fire began as a small flame about twenty minutes into the show, on the southwest sidewall of the tent, while the Great Wallendas were on. Circus Bandleader Merle Evans is said to be the person who first spotted the flames, and immediately directed the band to play Stars and Stripes Forever, the tune that traditionally signaled distress to all circus personnel. Ringmaster Fred Bradna urged the audience not to panic and to leave in an orderly fashion, but the power failed and he could not be heard. Bradna and the ushers unsuccessfully tried to maintain some order as the panicked crowd tried to flee the big top.

Sources and investigators differ on how many people were killed and injured. Various people and organizations say it was 167, 168, or 169 persons (the 168 figure is usually based on official tallies that included a collection of body parts that were listed as a "victim") with official treated injury estimates running over 700 people. The number of actual injuries is believed to be higher than those figures, since many people were seen that day heading home in shock without seeking treatment in the city. 100 of the dead were older than 15. The only animals in the big top at the time were the big cats trained by May Kovar and Joseph Walsh that had just finished performing when the fire started. The big cats were herded through the chutes leading from the performing cages to several cage wagons, and were unharmed except for a few minor burns. The cause of the fire remains unproven. Investigators at the time believed it was caused by a carelessly flicked cigarette but others suspected an arsonist. Several years later while being investigated on other arson charges, Robert Dale Segee, who was an adolescent roustabout at the time, confessed to starting the blaze. He was never tried for the crime and later recanted his confession.

Because the big top tent had been coated with 1,800 lb (816 kg) of paraffin and 6,000 US gallons (23 m³) of gasoline (some sources say kerosene), a common waterproofing method of the time, the flames spread rapidly. Many people were badly burned by the melting paraffin, which rained down like napalm from the roof. The fiery tent collapsed in about eight minutes according to eyewitness survivors, trapping hundreds of spectators beneath it.

The circus had been experiencing shortages of personnel and equipment due to World War II. Delays and malfunctions in the ordinarily smooth order of the circus had become commonplace. Two years earlier, on August 4, 1942, a fire had broken out in the menagerie, killing a number of animals. Circus personnel were concerned about the 1944 Hartford show for other reasons. Two shows had been scheduled for July 5, but the first had to be cancelled because the circus trains arrived late and could not set up in time. In circus superstition, missing a show is considered extremely bad luck, and although the July 5 evening show ran as planned, many circus employees may have been on their guards, half-expecting an emergency or catastrophe.

It is commonly believed that the number of fatalities is higher than the estimates given, due to poorly kept residency records in rural towns, and the fact that some smaller remains were never identified or claimed. It is also believed that the intense heat from the fire combined with the accelerants in the paraffin and gasoline could have burned people completely, as in cremation, leaving no substantial physical evidence behind. Additionally, free tickets had been handed out that day to many people in and around the city, some of whom appeared to eyewitnesses and circus employees to be drifters, who would never have been reported missing by anyone if they were killed in the disaster. The number of people in the audience that day has never been established with certainty, but the closest estimate is about 7,500 to 8,700.

While many people were burned to death by the fire, many others died as a result of the ensuing chaos. Though most spectators were able to escape the fire, many people were caught up in the hysteria and panicked. Witnesses said some people simply ran around in circles trying to find their loved ones, rather than trying to escape the burning tent. Some escaped but ran back inside to find family members. Others stayed in their seats until it was too late, assuming that the fire would be put out promptly, and the show would continue.

Because at least two of the exits were blocked, by the chutes used to bring the large felines in and out of the tent, people trying to escape could not bypass them. Some died from injuries sustained after leaping from the tops of the bleachers in hopes they could escape under the sides of the tent, though that method of escape ended up saving more people than it killed. Others died after being trampled by other spectators, with some asphyxiating underneath the piles of people who had fallen down over each other.

Most of the dead were found in piles, some three bodies deep, at the most congested exits. A small number of people were found alive at the bottoms of these piles, protected by the bodies that were on top of them when the burning big top ultimately fell down on those still trapped beneath it. The emotional toll on performers and spectators should not be underestimated, and because of a picture that appeared in several newspapers of sad tramp clown Emmett Kelly holding a water bucket, the event became known as "the day the clowns cried."

Category: The 20th Century